|

Box2D 2.4.1

A 2D physics engine for games

|

|

Box2D 2.4.1

A 2D physics engine for games

|

The b2Fixture, b2Body, and b2Joint classes allow you to attach user data as a uintptr_t. This is handy when you are examining Box2D data structures and you want to determine how they relate to the objects in your game engine.

For example, it is typical to attach an actor pointer to the rigid body on that actor. This sets up a circular reference. If you have the actor, you can get the body. If you have the body, you can get the actor.

You can also use this to hold an integral value rather than a pointer.

Here are some examples of cases where you would need the user data:

Keep in mind that user data is optional and you can put anything in it. However, you should be consistent. For example, if you want to store an actor pointer on one body, you should keep an actor pointer on all bodies. Don't store an actor pointer on one body, and a foo pointer on another body. Casting an actor pointer to a foo pointer may lead to a crash.

User data pointers are 0 by default.

For fixtures you might consider defining a user data structure that lets you store game specific information, such as material type, effects hooks, sound hooks, etc.

You can define custom data structures that are embedded in the Box2D data structures. This is done by defining B2_USER_SETTINGS and providing the file b2_user_settings.h. See b2_settings.h for details.

Box2D doesn't use reference counting. So if you destroy a body it is really gone. Accessing a pointer to a destroyed body has undefined behavior. In other words, your program will likely crash and burn. To help fix these problems, the debug build memory manager fills destroyed entities with FDFDFDFD. This can help find problems more easily in some cases.

If you destroy a Box2D entity, it is up to you to make sure you remove all references to the destroyed object. This is easy if you only have a single reference to the entity. If you have multiple references, you might consider implementing a handle class to wrap the raw pointer.

Often when using Box2D you will create and destroy many bodies, shapes, and joints. Managing these entities is somewhat automated by Box2D. If you destroy a body then all associated shapes and joints are automatically destroyed. This is called implicit destruction.

When you destroy a body, all its attached shapes, joints, and contacts are destroyed. This is called implicit destruction. Any body connected to one of those joints and/or contacts is woken. This process is usually convenient. However, you must be aware of one crucial issue:

Caution: When a body is destroyed, all fixtures and joints attached to the body are automatically destroyed. You must nullify any pointers you have to those shapes and joints. Otherwise, your program will die horribly if you try to access or destroy those shapes or joints later.

To help you nullify your joint pointers, Box2D provides a listener class named b2DestructionListener that you can implement and provide to your world object. Then the world object will notify you when a joint is going to be implicitly destroyed

Note that there no notification when a joint or fixture is explicitly destroyed. In this case ownership is clear and you can perform the necessary cleanup on the spot. If you like, you can call your own implementation of b2DestructionListener to keep cleanup code centralized.

Implicit destruction is a great convenience in many cases. It can also make your program fall apart. You may store pointers to shapes and joints somewhere in your code. These pointers become orphaned when an associated body is destroyed. The situation becomes worse when you consider that joints are often created by a part of the code unrelated to management of the associated body. For example, the testbed creates a b2MouseJoint for interactive manipulation of bodies on the screen.

Box2D provides a callback mechanism to inform your application when implicit destruction occurs. This gives your application a chance to nullify the orphaned pointers. This callback mechanism is described later in this manual.

You can implement a b2DestructionListener that allows b2World to inform you when a shape or joint is implicitly destroyed because an associated body was destroyed. This will help prevent your code from accessing orphaned pointers.

You can then register an instance of your destruction listener with your world object. You should do this during world initialization.

Recall that Box2D uses MKS (meters, kilograms, and seconds) units and radians for angles. You may have trouble working with meters because your game is expressed in terms of pixels. To deal with this in the testbed I have the whole game work in meters and just use an OpenGL viewport transformation to scale the world into screen space.

If your game must work in pixel units then you should convert your length units from pixels to meters when passing values from Box2D. Likewise you should convert the values received from Box2D from meters to pixels. This will improve the stability of the physics simulation.

You have to come up with a reasonable conversion factor. I suggest making this choice based on the size of your characters. Suppose you have determined to use 50 pixels per meter (because your character is 75 pixels tall). Then you can convert from pixels to meters using these formulas:

In reverse:

You should consider using MKS units in your game code and just convert to pixels when you render. This will simplify your game logic and reduce the chance for errors since the rendering conversion can be isolated to a small amount of code.

If you use a conversion factor, you should try tweaking it globally to make sure nothing breaks. You can also try adjusting it to improve stability.

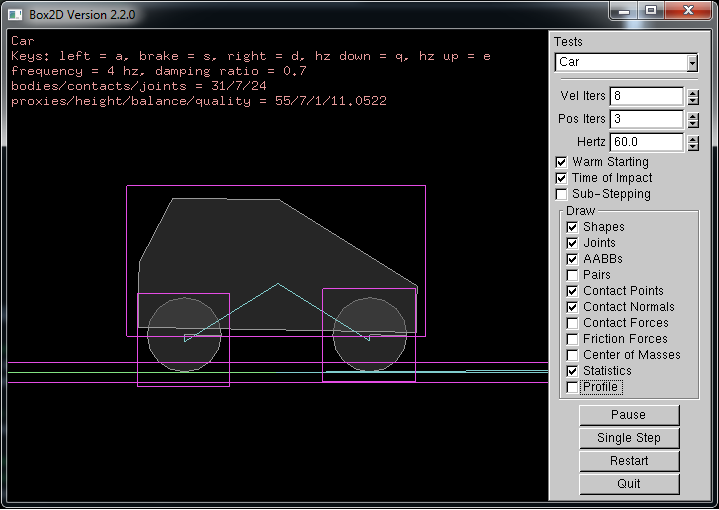

You can implement the b2DebugDraw class to get detailed drawing of the physics world. Here are the available entities:

This is the preferred method of drawing these physics entities, rather than accessing the data directly. The reason is that much of the necessary data is internal and subject to change.

The testbed draws physics entities using the debug draw facility and the contact listener, so it serves as the primary example of how to implement debug drawing as well as how to draw contact points.

Box2D uses several approximations to simulate rigid body physics efficiently. This brings some limitations.

Here are the current limitations: